|

Pam Nath has been living and working in New Orleans for the past seven years. She works for Mennonite Central Committee Central States and is a Roots of Justice trainer. She wrote this post for distribution to various Mennonite church publications as well as ROJ. The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor. Luke 4:18-19 “…the hands of none of us are clean if we bend not our energies to righting these great wrongs.” W.E.B. DuBois

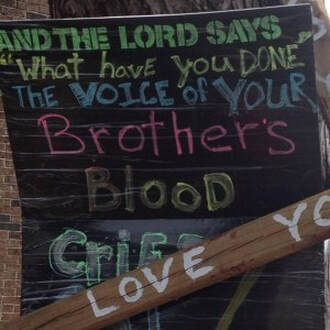

We talked with a number of Ferguson residents, including a group camped out in a parking lot across from the police station and some youth camped in the “approved assembly area” in the parking lot of an old car dealership. Both of these groups said they planned to stay until Darren Wilson, the police officer who killed Michael Brown was indicted, and we brought them water and ice and fruit as a way of expressing our support and appreciation for their persistent call for justice. That evening, we saw how W. Florissant Avenue was closed to all thru traffic beginning at its intersection with Chambers Road, a full mile away from the “approved assembly area.” Anyone who wanted to join the protest had to walk the mile in order to protest in a spot cut off from the rest of the public, where police imposed a “5 second rule” which required protestors to keep moving, breaking up any conversations among groups of protestors who began to gather together. This was only the most recent attempt to contain and squash people’s cries for justice. Others who had been in Ferguson earlier reported even more intense police repression. Police shot tear gas and rubber bullets at unarmed people who were in places they had every right to be including their own backyards, driveways and doorways. Purvi Shah of the Center for Constitutional Rights was part of a multigenerational crowd, including a number of children, into which police fired tear gas with no warning and a full three hours before the midnight curfew that had recently been established. Many first person stories of encounters with police oppression are available if you look for them. What we saw in Ferguson was a community under occupation by police. No one felt safer. The constant threat of violence by police toward protestors was palpable. The power of the state arrayed against the people of Ferguson reminds me of Desmond Tutu’s quote about an elephant with its foot on the tail of a mouse. Rev Tutu advised us: “If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor. If an elephant has its foot on the tail of a mouse, and you say that you are neutral, the mouse will not appreciate your neutrality.” What is extraordinary about Ferguson is not the killing of an unarmed black youth or the ways that institutions like the police, city government, etc. act in racist ways. That happens in New Orleans and it happens across the country. What is special and inspiring about Ferguson is that people’s thirst for justice is so strong there that they persist in protests despite the ways they are persecuted and threatened by the powerful militarized forces arrayed against them. Like Jesus, they are guided not by what is, but by their vision of what can and should be, and because of this, they, like Jesus, have found the courage to speak out in defiance of the powers of Empire, even to the point of risking their lives. They have done this now for two weeks. The evening of Friday, August 22, the thirteenth day after Michael was shot, we joined protestors who had left the approved assembly area and marched three miles to the Ferguson Police Department, to drums and chants like “We want justice!” “No Justice, No Peace!” and “Indict that cop.” Despite the fact that they were met at the police department by a line of armed police who stood in formation, blocking their access to the building, people gathered across the street and continued to cry out for justice through song, drumming and conversation. One young man said on the mic “we are not going to go over there. Let’s be clear that we have a right to go over there, but we are not going to exercise that right tonight.” I am reminded of a powerful sermon response that Vincent Harding delivered at the Eighth Mennonite World Conference in Amsterdam in the summer of 1967: The beggars are rising – they refuse to lie on the ground, crippled, crushed, begging. They are rising in Detroit and in Harlem…. and among them is Christ, the beggar of Nazareth. Do you see him? Do you hear him in the noise of all the voices? Do you realize how his spirit blasts all bastions of security, affluence, and greed? He is there. We can hide but he is there. We can continue paying our taxes for armies and bombs, and continue to cry: ‘What can we do?’ We can call on the police and the army. Fearfully we can hide behind law and order or behind the walls of our churches. Nevertheless, there is a spirit walking freely upon the earth. There is a spirit in search of freedom. This spirit will not perish…. We should know one thing – the insurrectionist beggars are not waiting any longer. Christ has promised to help all beggars and he keeps his promise. Let us not misunderstand. He is on the side of the beggars. On which side are we as Mennonites, Christians, and humans who love humanity? …. Are we surrounded by the barricades of a status quo where we pray that the storm may pass on so that we can continue living without disturbance? …. In this case, we must admit that we are…. missionaries of law and order, defenders of a status quo, and seekers for peace without a cross.

As people who believe in the gospel of peace, now is a time that presents an amazing opportunity for Mennonites to give flesh to our beliefs. Let’s not repeat the mistakes of the past when way too few Mennonites responded to Vincent Harding’s call to join in the civil rights movement. Let’s not repeat the mistakes of the Christians to whom Martin Luther King, Jr., wrote his “Letter from Birmingham Jail”: I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not the White Citizens Councillor or the Ku Klux Klanner but the white moderate who is more devoted to order than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says, ‘I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I can’t agree with your methods of direct action’; who paternalistically feels that he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom….Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection. In order to respond to the Gospel call for Justice coming out of Ferguson, we need to get clarity about what true peacemaking looks like. Peace is not refusing to be in open conflict or refusing to take sides in conflicts which exist. The situation in Ferguson doesn’t call for neutral mediators, bridge-builders between two sides who are in conflict, with us in the role of “peacemakers.” The “two sides” don’t have equal power, and they aren’t both right. Like Desmond Tutu, historian and social justice worker Howard Zinn warned against neutrality in the face of oppressive power. In Declarations of Independence: Cross-Examining American Ideology (a helpful read for those who wish not to conform to the world but instead to be “transformed by the renewing of our minds,” Romans 12:2), Zinn writes: Why should we cherish “objectivity,” as if ideas were innocent, as if they don’t serve one interest or another? Surely, we want to be objective if that means telling the truth as we see it, not concealing information that may be embarrassing to our point of view. But we don’t want to be objective if it means pretending that ideas don’t play a part in the social struggles of our time, that we don’t take sides in those struggles. Indeed, it is impossible to be neutral. In a world already moving in certain directions, where wealth and power are already distributed in certain ways, neutrality means accepting the way things are now. It is a world of clashing interests – war against peace, nationalism against internationalism, equality against greed, and democracy against elitism – and it seems to me both impossible and undesirable to be neutral in those conflicts. When we choose neutrality and are unwilling to engage conflict, we are clinging to the false peace that Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Old Testament prophets warned against. “They have treated the wound of my people carelessly,” Jeremiah warned, “saying, ‘Peace, peace,’ when there is no peace.” (Jeremiah 6:14) We need to face the cracks in the very structure of our society, rather than just trying to cover up cracks in the walls, as Ezekiel warned: “…they have misled my people, saying, “Peace,” when there is no peace; and … when the people build a wall, these prophets smear whitewash on it.” (Ezekiel 13:10) What would working toward a positive peace in Ferguson look like? Chris Crass, a white antiracist organizer, gives us one vision: So I’m seeing all these pictures from last night of adults trying to convince young Black people to leave the streets and only protest during the day in Ferguson, and this is being heralded by the police and mainstream media as “helping bring peace to Ferguson.” Where are the pictures of the white community leaders, the Federal government and the United Nations standing before the police in Ferguson telling them to put their guns down, go back to their homes, to take their frustrations out in constructive ways and to stop making us (the white community and the U.S. government) look like vicious, armed to the teeth, defenders of a white supremacist society without an ounce of regard for Black lives? “Peace,” as defined by the state and mainstream media, in Ferguson, means a return to the, below the national radar, war against the Black community that is “normal life” in this town that the Mayor repeatedly affirms “has no racial conflict.” Conflict, we are to understand, only exists when oppressed people fight back, but when oppressors rule through racist laws, policies, culture, and violence, it’s “peace.” That is why ever since the Rodney King rebellion in Los Angeles in 1992, the slogan is “No Justice, No Peace.” The Black young people in Ferguson, bringing discipline, non-violence, and determination in the face of continued violence and media smearing, are heroes! The positive peace that Jesus calls us to work toward requires the presence of justice. Here are just a few of my ideas about some ways to work for justice that holds the promise of real piece. I am excited to hear others’ ideas as well.

Let us not repeat the mistakes of our past. Let us join in this movement for change, this movement for justice, this movement for real peace, this movement where we will experience Jesus walking next to us and the Truth shall set us Free. Additional Recommended Readings

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRoots of Justice trainers and friends share reflections on historical and current events Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

© Roots of Justice, Inc. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed